And are not satisfied with my flesh?

Oh that my words were now written!

Oh that they were inscribed in a book!

That with an iron pen and lead

They were graven in the rock forever!

~ JOB XIX: 22-24

This is a chronicle of the tragedy of millions of Jewish people during Hitler's "Kampf" in Poland (much of which I witnessed), and of the great personal loss of all my loved ones in the infamous Majdanek Extermination Camp at Lublin.

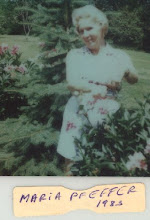

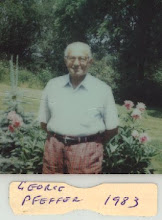

Had it not been for Maria's indomitable spirit, I should never have had the courage to come to America and begin life over again.

We are grateful to all the good people in America who have contributed to establishing us in a new and heretofore unknown life, where a man may stand to his full height and walk in freedom and dignity.

George Pfeffer, Sr.

Dayton, Ohio

September 11, 1958

by George Pfeffer 1944

translated by Pauline Kleinmaier 1958

edited and posted by Elizabeth Behr 2009-2011

** ** ** ** **

WARSAW 1944

I am George Pfeffer.

I am the quarry of the Nazis.

I run in the night from covert to covert -- panting like a wild thing fleeing from the hounds. I cower and pray and wait interminably for the end of the war.

My story might have been written by millions of other Jews. The basic pattern of their travail would have been the same as mine. Only the details might differ.

For them and for them alone I hold the pen, as though they held it. I should like to write it with an iron pen -- that our story could be graved in rock -- that future generations might read and not forget.

Just now I am hiding with several other Jews in the apartment of a Polish widow. With every knock on the door our sanity is assaulted. We quail in our hiding places and pray that we shall be overlooked again. Writing this story may help me to hang onto my reason.

My thoughts turn back to the end of World War I, when I was ten years old and Poland was put together again. Our teacher, Mr Pawloski, told us all about it. For 125 years Poland had been occupied by its surrounding neighbors. Geography and history were NOW for us. We were part of history being made. We were proud to be Poles. A patriotism was aroused in us, such as only a child feels when he first becomes aware of his nationality.

At home our parents and friends discussed the new turn of events. Would this new Poland bring citizenship for the Jewish inhabitants? Would a happier, freer Polish people abandon their old persecutions?

Mr. Pawloski told us how Ignace Jan Pederewski had left his piano and, as premier of Poland, went to the Paris Peace Conference. There, in exchange for important territorial grants, he was asked to sign a pledge that all minorities within the boundaries of Poland would be given equal rights, including those of different faiths. He signed.

Upon his return to Poland he made these provisions a part of the new Constitution. The Jews wondered if this new law was written in good faith.

Counting those in the re-united sections, Poland now had the largest population of Jews in Europe: over three million. Yet post-war privations made the Poles restless. They turned again to their old punching bag, the Jew, to pound out their frustrations. There were economic boycotts against the Jews; hoodlums stoned Jewish stores; signs were put up reading "Nie Kupuj U Zyda" (Don't buy from a Jew). These things and the daily insults made life utterly miserable for the destitute Jews.

Marshall Josef Pilsudski tried to uphold the Constitution to stem the rampant discrimination. He did not seem able to implement the new law which provided full rights to Jews. Yet these rights had been earned with the blood shed by Jewish soldiers who had fought shoulder to shoulder with the partisans to regain Poland's lost territories.

The economic situation for the Jews became increasingly acute. What could they do? Because other nations had closed their doors to immigration, they could not flee the country.

This was the background of my boyhood in Warsaw. Within the limits of my childish comprehension, I was conscious of these things.

Our family was prosperous. My father, Abraham Pfeffer, had a leather goods factory, employing 80 people. He also owned income property. Yet in spite of their own comparative security, our elders were deeply disturbed by the perilous position of the entire body of Jewish Poles, prone as they were to continuous harassment and economic ruin.

In the summertime we led a sheltered life in a small villa my father owned on a tributary of the Vistula at Miedzeszyn. Our old nurse Jadzia Zagierska came with us. The Polish janitor and his wife, Michael and Michaelowa Glazewski, lived in a nice little cottage. They tended the apartments and gardens, the tennis courts and fruit orchards.

My sisters, Stefania and Helen, and I were Michael's shadow. He taught us to swim and fish, and to row a boat on the broad Vistula a few miles away. We had a deep affection for him.

When I was 16 our dear mama passed away. One day the principal of our Gymnasium called me from class and sent me home to learn that Mama had been rushed to the hospital for an emergency operation. She had asked to see me.

When I saw her face, pale and distorted with pain, I sensed that she was about to die. She was very brave and tried to shield me from the truth. She asked me always to look after Stefania and Helen, no matter what should happen. In that moment I became a man with a grief and a burden.

In time, my father married again, but he remained very close to us. His warmth and love compensated, in part, for the loss of our mother.

After I graduated Gymnasium my father sent me to the College of Commerce in Warsaw. In 1932, at the age of 30, I received my Master's Degree in Economics and Accounting. After the commencement exercises, Father took me to his factory. As we stood before the building he put his arm across my shoulders and pointed proudly to a new sign above the door, which now read: Abraham Pfeffer and Son. That was a glorious day.

By 1933 Hitler's fire of anti-semitism spread through Central and Eastern Europe, [as he] created a smokescreen of lies to cover his foul machinations. Out of our radio receivers his terrifying voice spewed his malevolence in harsh guttural Austrian accents. Our Polish newspapers screamed his headlines of hate.

At this time, however, my ears were also attuned to pleasanter sounds. They emanated from a concert grand piano at the Philharmonic in Warsaw. The music was Chopin, the pianist a beautiful young virtuoso named Luta Chigryn. According to the program, she had placed fifth in an international competition held annually in memory of Frederick Chopin.

Her performance was at times gay and capricious, or full of poetry and romance. When she played a nocturne I closed my eyes and seemed to see her in a garden with fountains dripping in moonlight.

In a daze I entered the reception line after the concert and managed an introduction. Then I stepped aside and observed her from a distance. I noted the simple dignity with which she accepted the compliments paid her, her unaffected charm and poise.

Luta had the courtliness of a Polonaise, the sparkle of a Mazurka, the lyric beauty of a Chopin ballade. How dare I dream of breathing the same air as such a rare creature? But I did dream. And dreaming made her mine. Luta -- lovely Luta! We married as soon as she was graduated. That was 1935.

My father was generous. We honeymooned at the Europejski Hotel at Zakopane in the Tatry Mountains. It was the end of February and winter sports were at their height. We skied and tobogganed, dined and danced, attended plays and concerts. In our lovely and loving dreamland, Hitler was merely an ogre conjured up to frighten little children.

Upon our return, we spent part of Luta's dowry to furnish our apartment on Komitetowa Street. Her grand piano dominated our home, as did her exquisite music. Her music poured over us, drowning out the strident, threatening radio. In those days, we lived in a world of our own. At the end of our first year of marriage, our son was born. Ignas, with his blue eyes and fair hair, was a joyful baby. Our happiness was complete.

In 1938, when Ignas was two, there occurred in the Polish cities of Brest-Litovsk, Czestochowa, and Prystyk the most appalling pogroms against the Jews of these cities. The thoroughness and technique of these mass killings and atrocities were Hitler-inspired, without question. We were profoundly disturbed. But we tried to quiet our fears with the delusion that this could not happen in Warsaw, even as the horrendous threat to our happy future began to dawn upon us.

Our family had grown considerably in the years since my mother's death. Two children had been born to my father and "Aunt Dora," as we called our step-mother. A girl, Edra, and a boy, Izio. After our marriage, my wife Luta had been added to our circle and then our baby, Ignas. Stefania had married, and our younger sister, Helen, was engaged.

Summer: the entire clan was together at Miedzeszyn. The men of the family commuted to their businesses in Warsaw, some 20 miles distant. That last summer, 1939, Hitler had "freed" Sudetenland, swallowed Austria and Czechoslovakia. Now he demanded the Polish Corridor. With some sense of security because of the mutual aid pacts with France and England, Poland mobilized.

At our summer place, we tried to put up a brave front. A little tennis, a little picnicking in the orchard. We fooled no one, much less ourselves. Our hearts were heavy. There was no escape, no where to run. Minutes and hours became precious jewels. Days were priceless.

Luta played for us in the evenings. As always, her music entranced and possessed us. But now it had a brooding quality, a vein of sadness underlying the notes, intensifying our feelings of hopelessness and doom. A bone-aching nostalgia welled within us, such as only a disinherited Jew can know -- a homesickness known only to the homeless.

That last week of August, Father and Aunt Dora returned to Warsaw. I talked to my father daily by telephone. He reported that business was at a complete standstill. and that he had to discontinue extending credit to his customers. The banks had stopped all loans. Father advised me to stay where I was and look after the family.

Blitz Krieg struck at midnight, September 1, 1939. By sea, air, land Nazi's swarmed over our western border. From the Baltic, south to the Carpathians they drove forward. Ahead of them swooped the shrieking dive bombers. Taken by surprise, our airfields were quickly put out of action. Our army fought bravely but were forced back by the Nazi tanks. By the second or third day . . . the enemy was approaching Warsaw.

The people did not want to believe at first that this was enemy action. They thought the Luftwaffen were Polish planes on maneuvers. Not until they saw swastikas on the wings of the planes, not until they saw large buildings falling down like toy blocks, not until they saw the streets bloodied by the innocent dead: not until all this did they realize we were at war.

Over the radio came the call from President Stefan Starzynski -- all able-bodied men must flee to eastern Poland to be mobilized. I left the villa and went at once to the city. Warsaw was paralyzed. All communications had been severed. The city was in flames. Gas and electricity had been cut off. Half-dazed people ran crazily through the streets.

When I arrived at my father's home, I told him I was going east. He said he would also go. My brother-in-law said the same. We left Warsaw on foot, taking food enough for only a couple of days. We past River Bug, there the highways were crowded with people fleeing with their babies and bundles. Overhead, the bombers strafed us. As we hurried along, we wondered if we would ever see our families again.

Mid-September we reached the place of mobilization only to find we were cut off by the Russian army. By arrangement with Hitler, previously their enemy, the Russians occupied all of Poland east of the River Bug. The enemies of yesterday were friends and allies today, and both now were enemies of Poland. What had happened to our friends, France and England? We were shut off from the world and knew nothing of what was going on outside.

The return journey took us two weeks. We had to take a circuitous route to avoid capture by the Russians. We arrived home to find the entire family in Father's basement. We were welcomed with tears of relief.

Luta told me of events after I had left Miedzeszyn. When the bombing started, the rest of the family there decided to return to Warsaw. With the help of the servants, they hurriedly closed the house and started walking the 20 miles to the city. Ignas was frightened by the bombs and Luta had carried him in her arms most of the way.

At Father's home they found Aunt Dora and her younger children huddled in the basement in a makeshift bomb shelter. They had gathered a sufficient food supply and water from an artesian well, so they had survived the unnerving bombing raids.

By September 28 Warsaw fell and the bombing stopped. Luta, the baby, and I returned to our own apartment. Our building was still intact. We resumed our lives, but with many restrictions. Jews were not allowed to travel out of Warsaw. Within the city limits, they must use special street cars. We had to wear blue and white armbands. The Nazis were now in full command.

The end of September, all Jews living in Warsaw -- 350,000 -- were ordered into a part of town defined by certain boundaries. All non-Jews living in this neighborhood had to move out. With overcrowded conditions and increasing poverty, the area, which had once been a nice residential district, became a ghetto. My father's apartment, as well as my sister Stefania's and ours, were all situated within the boundaries of the restricted Jewish district. We did not have to move.

All Jewish-owned businesses outside this section were confiscated. Our leather goods factory was taken over by the Nazis, as well as the real estate my father owned and, of course, our summer villa.

Our old Polish Aryan nurse, Jadzia, who had become sort of confidential secretary in my father's business after the children were out of the nursery, pleaded with Father to let her remain in the Jewish district with us. She was 65 and had no home but ours. I saw several officials on her behalf and we received permission to keep her. We trusted her like a member of the family and were touched by her loyalty.

Every day the terror for the Jews increased. No night passed that some homes were not entered and the men killed in the presence of their families. Many professional Jews, doctors and lawyers, were taken from their homes in the middle of the night and never heard from again. Young Jewish men were taken for slave labor.

Little by little, at first, the liquidation began. First old people and the weak and sick were eliminated. I remember hearing of a case where a feeble old man in a wheel chair was thrown from a fifth-story window, chair and all, before the eyes of his terror-stricken loved ones. Then came the order to build a wall around the ghetto. Soon after that, Nazis called for volunteers to form a Jewish police force to keep order in the ghetto. Many young men volunteered, believing they could be of service to their people.

Jews from small towns were brought into the ghetto pen. Conditions became unbearable. As many as ten families, total strangers, were crowded into five rooms. The population quickly grew to half a million. My father took three families into his apartment. We took in one family, in addition to Luta's parents and her brother's family.

The food situation became acute. People died of starvation. Children fell dead in the streets.

Typhus, born of starvation and filfth, of vermin-infested, unwashed bodies in too-close proximity, aided the Nazis in their goal to rid the earth of Jews.

Somehow we survived. My father was able to turn his valuables into cash on the black market. This kept us from starving. Some food and necessities were smuggled in from the Aryan side of town.

In the winter of 1940-41 an order came that all Jews who owned furs must turn them over to the Nazis. Failure to comply meant death.

Eastern European winters are long and bitter. Anyone who could afford furs had them. The women of our family had fine ones. The men, too, had fur-lined great coats with large fur collars and cossack hats. Why should we provide Nazi soldiers with fur linings for their uniforms? Let them freeze!

Through Jadzia, my sister sent hers to a friend on the Aryan side of town for safe-keeping. My sister and I were the only ones who knew this, and only Jadzia knew where the furs were hidden.

Some months later, when the action against the Jews increased, Jadzia had to say goodbye and move from the ghetto. After she left us, we kept in contact by telephone. And later when the telephones were cut off, we wrote letters. At one time I told her to sell a Persian lamb coat. We needed the money and this was the only way to raise it.

For several weeks after, I did not hear from her and could not locate her. I asked some Aryan friends to try to find her, and after some time they did. Following my instructions, they pressed her for the money. She sent part of it. We never saw the rest.

Early in 1942 the liquidation of the Jews began in earnest. The Nazis were systematic. Daily action took place now on a much larger scale. Selections were made from the unemployed, the weak, the aged. During this time, Luta's parents were taken from our home by the Gestapo. How my darling cried.

A thousand or so Jews were sent to the Umshlag Platz. This was an open square where the unfortunate chosen were herded by storm troopers and Jewish police into boxcars like cattle, then taken to God-knows-where.

By summer that year the tempo increased. As the population shrank, the ghetto area was made smaller and smaller. All able-bodied men and women were now employed in factories, or shops, run by the Nazis. These shops were set up in vacant apartment buildings in the ghetto. Luta and I were working in separate areas in our shop. That summer I kept Ignas close to me. Children were on the priority list. He was nearly eight now. Luta decided Ignas would feel more secure with me. He and I hid together whenever danger seemed imminent -- making a sort of game of it.

On a certain Sunday that year, all the Jews employed in our shop --3,500-- were ordered to go to a place in the vicinity of Umschlag. Only 600 gathered there were to receive slips of paper which would permit them to return to work. The remaining 2,900 would be sent to the Umschlag Platz and the boxcars. The lucky ones with the name cards were to be billetted in the factory building.

I soon found out that Luta's and my name were not among the 600. So the three of us were destined to go to Umschlag. UMSCHLAG! DOOM!

The names were written on small slips of paper, together with the person's number. One of the foremen climbed on a box and called out the name on each slip. That person, if present, was to reply with the number on his identification card. If the number and name checked, the foreman delivered the slip to that person. Little slips of paper: the difference between life and death. Luta and I thought we were lost. I determined to get a slip for each of my family, if I could.

I stood close to the foreman and tried to memorize the names not claimed. I looked over his shoulder to read the number assigned to that name. I noticed he put the unclaimed slips under the stack in his hand to be called again later. After memorizing four names and their corresponding numbers, I managed to collect four slips. One for Luta. One for Aunt Dora. One for my sister-in-law. One for myself.

My father was lucky enough to have had his name called.

I was unable to get a paper for my brother-in-law, so I tore a piece of paper the same size as the others, wrote down his name and number. With a mechanical pencil I forged an "official" stamp on this card, copying the stamp marks on the four I held. It was easy to see it was made by a pencil, but I figured we had nothing to lose.

Aunt Dora was in the hospital. She'd had a slight operation on her leg several days before. She was still there when we were told to assemble for name cards. When the order came, my father ran at once to the hospital to get her. The hospital staff had orders to release no patients. All the sick were to be taken by escort to Umschlag.

Father was not able to enter the hospital. Aunt Dora, who had been expecting him, came to a window on the second floor. Father signed to her to come to the window of an empty room he could see on the first floor. Wearing a house robe, she came down to the window indicated. She had no other clothing. With Father's assistance she jumped from the window. They got away unobserved.

On their way to their home to get her some clothing, he broke the news he had withheld while she was in the hospital: Their two children, Izio 13 and Edra 16, had been taken to Treblinek concentration camp. The shock of this tragedy in her weakened condition unbalanced her. Father had to carry her the rest of the way and, once home, force her to dress. After quieting her, he helped her to the meeting place. I gave her the bogus "slip of life."

After the slips of paper had been delivered to the lucky six hundred, the Jewish police formed a tight cordon around the crowd, allowing only those with slips to pass, counting them as they left. Those who had no slips of paper began rioting, attempting to break through the police line to save their lives, all to no avail. The police beat people over the head and finally called SS men to restore order.

Those with slips now crossed the cordon and lined up outside the square. I had a difficult time because they would not let me take Ignas. Then one of the policemen who knew me let us pass. Our lines were surrounded by Jewish police and overseers. The police told me there was no use trying to get Ignas through, the SS would hold him and us as well.

I tried to hide him in the suitcase I had with us, throwing out all the contents, but he was too big. I rolled him in a blanket to take him on my back, but the bundle was too large. Besides, it was obvious the bundle was a child. A Jewish policeman told me the Nazis in previous selections had killed children so hidden, with their bayonets. There had been one such case earlier that day.

Having no alternative, I decided to lead him by the hand beside me. I made Luta agree that if I was taken out with our son, she was to stay in the file as though she did not know us. In my heart I believed I might escape with Ignas, even if we went to Umschlag.

Before the final check our factory chief gave the order that everyone must hold the name card in one hand and the slip ("slip of life") in the other. These credentials were then checked to make sure we held the right cards. When we realized there would be a showdown, we feared our deception would be discovered. Nevertheless, we held cards and slips as directed.

Our factory chief, who was a civilian German governement worker, checked the first four rows very carefully for the data on the cards to agree with the data on the slips. We were in the fifth row. When he came to our row, he checked only to see that each one held two documents. He did not compare them.

As he passed me he looked at Ignas, then at me, and without a word let me know I must get rid of him. I was unable to speak. With a pleading look I begged silently for mercy. I knew he had three children of his own. I prayed that he would understand. The pain he saw in my face and the horror in my boy's eyes must have moved him. The chief shrugged as if to say "we'll leave it to the SS men." Then he passed to the next row.

The SS men ordered me out of file and I stood aside with Ignas. Seeing that the SS men were busy checking others and paying no attention to me, I picked Ignas up, pressing him tightly in my arms, and dashed into the group already qualified to return to the shop. A Jewish policeman saw me do this, but no one interfered. Ignas and I mingled with the others. Luta was already there. Her eyes filled with tears when she saw us in the crowd again.

During the march to the shops I hid Ignas under my coat. The street along which we marched was full of SS men and Ukrainian soldiers and I was terrified that they would notice him. Ignas was the only child rescued in that day's action.

Our shop was set up for renovating damaged helmets for Nazi storm troopers. We hammered out the dents in these helmets with murderous blows, as though we were bludgeioning the heads destined to wear them.

Ignas became popular in the shop. Everyone loved him. The assistant director of the factory, an Aryan Pole, could scarcely believe the child had survived the action. He asked me to tell him again and again how I had accomplished it. I told him God had been with us. It was indeed a miracle.

Living conditions in the billetting places were harsh. A few sticks of furniture, left by the unfortunate ones who had lived there and had already been liquidated, served us for beds and chairs. Our lodgings crawled with vermin. Our family -- twelve of us -- was housed in two rooms.

We had been selling family jewels one by one on the black market for a fraction of their value. The few zlotys we received kept us from complete starvation. Now the jewels were almost gone. When we moved from our home to the billetting quarters we hid what little of value we had left between the lifts of our heels or in the seams of our clothing. Luta and Stefania hid $20 American gold pieces in their hair.

On April 19, 1943 the last liquidation phase started. In three and a half years Warsaw's population of 500,000 Jews shrunk to a few thousand. those who still survived were reduced to poverty, their clothing in rags.

Rumor came to us that the destination of the daily "shipments" was an extermination camp, although the official Nazi information was that the people were being re-settled in the east -- in work camps.

The remnant of the ghetto population, emaciated, destitute, and ill, suddenly came alive. Underneath our filthy, crawling shirts still lived a spark of courage. We determined to fight to the last. Guns were smuggled to us from the Polish side. Every man and woman able to fire a gun was armed.

Our Nazi overseers in the factory fled in fright. We were on our own. We manned the guns at entrances and windows of the building and fired at any Nazis who tired to approach. A number of Nazis were killed. We put a real scare into the SS bullies. They became wary and would not enter the ghetto except in armored cars. Many of those, too, were picked off by our guerillas. We knew from the first that we could not win. The attempt was what counted.

Block by block, now, the Nazis set fire to the factory buildings. Those who could ran out of the flames to to buildings in other blocks, only to be routed again and again by the spreading flames. Our family fled from our burning factory and ran to a bombed out basementin the next block. Helen and Stefania were with us.

After we were five days in this shelter the Nazis set fire to the entire block. We had to run for our lives again. All of us had burns on our legs and faces. We ran in terror to the next block, which had been razed two days earlier and was still smoldering.

Luta found a refuge of sorts for us -- a basement under the ruins. Normally this shelter could have held about 30 persons. Well over 100 injured and starving people crowded into this basement with us. They came, as we did, practically empty-handed, their only provisions a bag of dried bread or biscuits.

We knew we could not stay here more than a few days: No light, no food, no water, no lavatory, the stench of burned bodies under the ruins all made that impossible.

Lips moved in prayer to the Almighty, pleading for release from our unbearable sufferings. Death seemed preferrable.

The memory of May 2, 1943 will be with me always. The Nazis, under the guidance of a turncoat Jew (God knows what false promises they made), found us. Gestapo troops used tear gas to evacuate us. Luta and Ignas were choking for air. I dragged them from our hiding place. An SS man commanded us to raise our hands. We were thoroughly searched and stripped of everything they could find.

The officer in charge took me aside. He told me we were to go to Poniatowa, a concentration camp, but if I would tell him where similar shelters were located and lead the way, he would set me and my family free.

It was a great temptation but I could not bring myself to betray anyone. I told him I was a newcomer and did not know of other shelters. Soon, though, another man from our shelter agreed to help find and evacuate similar shelters in the vicinity.

After the Nazis had rounded up a number of people, the unmarried men were taken away and shot, since they had no close relatives and might try to escape. The rest of us were taken to Umschlag Platz. There we were searched again.

The Gestapo was joined by Ukrainian and Latvian volunteers who were, if possible, more merciless than the Gestapo. (We learned that the Ukrainian and Latvian armies had revolted against Russia and had taken sides with the Nazis as they expected Germany to win the war.) They beat us into semi-consciousness and, after several hours, we were loaded into the cattle cars to be taken away.

From the Platz to the railroad cars was only a city block, yet for us it was an interminable horror march. We were continuously beaten, shot at, and robbed. They took our shoes, our overcoats, our jackets, even our trousers. An SS man struck Aunt Dora on the head until the blood streamed over her face and dress. They hit me, too, with an iron rod. The day was one of those hot ones which comes early in May, yet they refused to give us water.

They herded us into the cars hours before train time. Ukrainian guards had already closed the small windows at the top of our car. I remember it was a French freight car with three windows at the top on each side. After closing the windows, the guards offered to open them for 1,000 zlotys each (about $100). No one seemed to have any money left. We struggled for breath. Some began to fight violently. Only then, somehow, money was found and the windows opened.

In the evening, after a horrorific day, we began to move. In a cattle car scarcely large enough for 40 people, 150 of us stood tightly packed together. No one spoke for a long time. We stood like mute beasts. We had been drained of all emotion and thought.

The moon shone through the high windows in shifting shades of light, lending an eerie, deathly pallor to our faces. Expressionless, our starved, bony heads seemed to float bodiless in a moon-washed purgatory.

Beneath us the relentless wheels rolled on and on, on and on, on and on --rattling our bruised and beaten bones. With the sometimes jerky movements of the train, we lost our footing and, having no place to fall, fell upon one another.

During the long night, some prisoners escaped by climbing through the small windows and jumping. I wanted to do this. I discussed the possibility with Luta. she opposed the idea, saying it was too risky. It was quite a height from which to jump. Also, she was afraid I would be shot by Ukrainian guards who, from the roofs of the cattle cars, fired after escapees. The strongest argument was our child. I wanted to throw him out the window and jump after him -- but Luta would not hear of it.

The Nazis were well aware of family devotion among Jews. They counted on these strong ties to prevent escape attempts. They were so right. Families remained together like sheep being led to slaughter.

Most of us were sure we were not being taken to a concentration camp, but only to a labor camp at Poniatowa or Trawniki. Others believed we had passed through the town of Otwock, which meant we were headed for Lublin. LUBLIN! We had heard unbelievable rumors of the camp at Lublin. At the thought, a cold shudder went through us.

With no room to lie down, we were kept in the railcar all night and a full morning, a time of excruciating misery to the sick and wounded. During the trip, six persons in our car died. Three others went insane. One woman became violent and started biting her neighbors. We had to bind her with some of our clothing. To protect our small son, to give him a little space to breathe and to keep him from being crushed to death, I had to keep my hands pressed against the wall of the car, pushing my back against others.

In daylight we arrived at our destination. We could hear the voices of the station attendants. We were in Lublin. But we were not unloaded. Our train was placed on a siding as though it was marked "Contents non-perishable. Unload when convenient." We were kept in the stifling railcar in the heat of the day four more hours. We prayed -- or thought we did. WHERE WAS GOD?

It was possible to obtain a little water here, but the Ukrainian guards and Polish railway workers demanded 100 to 500 zlotys for a half-pint from the station pump. After so many searches, few people had anything left to pay for the precious fluid. I was able to buy a few drops for Ignas, whose lips and tongue were parched and swollen.

At last we were released from the steaming, fetid boxcar. We saw the occupants of other cars already standing on the Lipowa Square. We were indeed in Lublin. With numbed and cramped legs, those of us still alive joined the ranks of the condemned.

We were lined up ten abreast, guarded every fifteen feet by SS with a light machine gun, and a police dog on a chain. The march started almost at once.

We proceeded along the highway outside the city. Some of the people fainted from exhaustion, exposure, and hunger. Those of us stil able to walk had to carry the fallen on our shoulders. I helped carry a half-dead woman. We were certain now, with such an escort, we were being led to our execution. Little Ignas, fully aware of the circumstances, asked his mother, "Mama, shall we be shot or gassed?" But the perverse Nazis did not want us to die too fast -- just a little at a time so they could enjoy our suffering.

At last we arrived on the camp square, where the counting and the searching started all over again. We had been assured that we were being brought here to work for Germany. But the next day we were told by Jews who had been here for some time that this was the most infamous of all extermination camps -- Majdanek. We knew then we were at the end of the line. No Jew who came in here went out alive.

Some of the people begged our captors for a drop of water. Begging was useless. Our one wish was for water. It had been 24 hours since most of us had any at all. I prayed to God that we would be taken to the gas chamber, that our misery would be ended. That prayer, too, was not answered.

Through the night, we were kept on the open square under the sky. It turned quite cold and a heavy rain drenched us. At the first drops we turned our faces thirstily to the heavens. But the rain pounded and became colder. We could not sit on the ground in the cold rainwater. Many people whose clothing had been stolen at Umschlag were half naked, their bare feet frozen.

The camp square where we stood was surrounded by towers every 50 meters (160 feet). Our first morning after the cold, wet night, guards in these towers began shooting into the crowd with machine guns -- just a little morning sport! Lucky the ones who were killed, their suffering over.

Finally they gave us water -- through fire hoses. We could scarcely stand against the force of the stream. Our clothing carried the excrement of two days. The soaking we received only made us more miserable. Still we had no drinking water, nor any food.

About midday we were divided into groups to go to the showers. Women and children were separated from men. I could not have known it then, but that was the last time I would see my beloved Luta and our dear little Ignas.

My father and I tried to stay close to one another. Our group of about 120 men was taken into the shower shed. The leader was an SS man on a motorcycle. All the guards were armed with whips. We had to run as fast as the mororcycle while the guards whipped us to keep up.

My father, who was 56, was not able to hold the pace, so I caught hold of his arm and dragged him along. I remember distinctly his last remark to me. "I prefer to die rather than suffer more, and there is no end to the suffering, as I can see."

By now we had reached the dressing shack. There, SS men with iron rods and whips drove us like cattle. We had to be undressed in one minute. The guards then searched us for hidden money or jewelry. They examined our mouths, ears, and rectums with brutal, dirty fingers. If they found something hidden, they gave the culprit a ghastly beating.

From the dressing shack we were whipped and driven into the showers. Here the old and disabled were separated out and sent to one side. This was their method of selection. It was the death verdict. My father was among those selected.

We still had a moment to communicate with one another, eye to eye in silent blessing and farewell across the space that separated us, until we were blinded with grief.

I cried within me the Hebrew confession of faith in time of trouble: Sh'ma Yisroel, Adonoy Elohonu, Adonoy Echod. Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is One. My one comfort was my father's last wish "to die rather than suffer more." One of his prayers was answered.

I was numb now. The human heart can bear only so much suffering and no more.

About 25 of the 120 men in our group were taken to the gas chamber and crematory that evening. In my heart and soul and mind I searched for God. When I found Him, He was crying. May 4, 1943 . . . always a day of remembrance of my father's passing.

Before we went into the showers, our hair was clipped short. Then we were searched again and given a medical examination of sorts. What a relief it would be to get under the shower after these ordeals. But that small hope was short-lived.

At first the water was frigid -- then it was scalding. We had no soap, no towels. Then we were given clothing and told to dress very fast: wood-soled shoes, dirty shirt, shorts, a cap, trousers, a jacket from which the lining had been torn. These were the legacy of the dead who had preceeded us.

The jacket of this outfit had a wide scarlet stripe painted on the back with the letters K.L. -- Konzentrazions Lager, concentration camp. Similar stripes were painted on the trousers, in the front on the right leg, on the back on the left leg. The cap bore the same stripe front to back. We also had insignia: two triangles, one red, one yellow sewn on either side of the jacket. Above this was a white band on which our identification numbers were printed. This was to distinguish Jewish prisoners from others in the camp.

As we came out of the shower shack in these outfits, we were attacked by officers and non-coms of the SS. Lined up on either side of our path, they tripped us, hitting and kicking those who fell down. We were then led to another structure where the main office was located. Czech Jews filled out questionnaires for us on special forms. We were measured, asked all kinds of personal questions. When the forms were completed, we each received a number. Thereafter, we were known only by our number. No more George Pfeffer. I was 2848. This was stamped on a piece of tin which I had to wear around my neck. I wondered how many others had passed into the gas chamber before me with that same number over their still beating hearts.

After this registration, we were led to the barracks: Rough sheds, neither air- nor water-tight, with small holes near the ceiling serving as windows. Three-decker bunks with a little straw and a straw pillow and some thin rag that was supposed to be a blanket. No plumbing.

We were ordered to turn in for the night-- still without food or drink. Our first day was over. Like dead bodies we fell onto our bunks.

At 3 A.M., they roused us. We dressed hurriedly, "made" our beds under strict supervision and cleaned the floor. (For the slightest fault in our work, we were given 25 strokes of the whip. After a month of such treatment we could scarcely sit or lie down.) On command, we rushed double-time into the cold dark morning. The moon was still bright. I looked up at the heavens. God was there going about the business of His universe. Why did He not hear our cries?

Huddled together in little groups for warmth, we crossed a path to the open air wash-room -- a few taps to accomodate 4,500 people on our Field No. 3. No soap. No towel. No toothbrush. No handkerchief. Gingerly we went through the motions of washing, a few of us at a time. About 5 A.M. we were given a half-pint of sour black ersatz coffee, nothing more. At 6 A.M. -- parade.

We lined up in five rows at attention, and remained in this position while the guards amused themselves with such orders as "Caps off! Caps on!" After that, they counted the men from various barracks. Our field had 22 barracks. About 200 men were assigned to each one.

They then divided us into groups for work. Some groups had to lay railway tracks, some worked on a new road, some were put to breaking and carrying stones or coal, cleaning lavatories, digging ditches. All this went on inside the camp, of course.

As a diversion, the guards beat the working men with whips and rods for no reason whatever. Fiendish laughter followed from the gallery of SS onlookers. If the beating continued until the victim fainted, he was kicked in the ribs, face, stomach, or more sensitive organs. Another prisoner would be ordered to pour cold water on the victim to revive him. Often the victim did not respond, having suffered broken ribs, knocked out teeth, holes in the head. In this eventuality, he was carried to the gas chamber.

The most popular game devised by the Nazis transformed a Jew into a punching bag. Two Jews were ordered to hold up a third Jew by the collar. After the first murderous blow to the jaw, the victim fell. Each time, he was picked up so the prize-fighting Nazi could continue training. The punching continued until the victim --teeth knocked out, nose broken, perhaps an eye hanging out of its socket-- had to be carried to the doctor to have his wounds dressed. Great sport. Great sportsmanship. They always gave the punching bag medical care so he could be beaten up another day.

Another popular Nazi game was kicking a Jew in the shins with heavy spiked boots while he stood at attention. If you were close enough, you could hear the crunch of breaking bones. These victims always died in agony. In these ways, the SS men had their daily exercise.

There was another group of guards called "Kapos" --Kaserna Polizei. They had been recruited from among Condemned German criminals. Taken from the prisons, they became overseers at Majdanek. Being Nazis they had special privileges, although they were not at liberty to leave the camp. Their living quarters were separate from ours. Their food and drink much better. They wore red or green trousers with high boots, such as those worn by horsemen.

One of the Kapos in our yard was an old fellow, a gangster in his former life. Often when he received an order to pour water over a victim, he would choke him with his bare hands instead. I saw this man catch a 13-year-old boy and swing him around by the legs until the young head crashed on a pole. From this the SS men learned a new game: how to finish a Jew with one swing.

A gallows stood in the middle of each field. Any Jew who was late for morning callup, or guilty of any similar "crime," was strung up by the camp commandant. One day a friend of mine from Warsaw was hung for coming late for callup. He was late because he had been so badly beaten the day before that he was unable to get out of bed.

The work done at the camp was neither constructive nor necessary. It was intended to exhaust us. When a prisoner fell from exhaustion, the guards had an excuse (as if they needed one) to beat him ...until he was ready for the gas chamber.

On those fortunate days when we had lunch, it was at noon. All prisoners lined up in front of the kitchen where we were given one-half liter (one pint) of cabbage soup, without any fat or flavor. No matter what the weather, we ate it outdoors and standing. We had no spoons. More exactly, every prisoner had a wooden spoon assigned to him. These were kept in the barracks to show to members of the International Red Cross Commission on their inspection visits to the camp.

Mostly there were so-called "Korne" days, when lunch was skipped entirely and only supper was given to us. The meal was cold, the food stale, but after a day of hard labor, it was devoured.

After lunch, if we'd had it, we returned to the same routine of work and beatings until 6 P.M. At that time we had to muster for the evening callup, standing at attention while the SS men counted and re-counted us. This ordeal lasted two hours. During this time some men were called out for some supposed wrong done during the day. Stripped of all their clothing, they were made to lie on special benches to receive their punishment-- usually 25 or 50 strokes of a whip.

Once during the morning callup one of the prisoners was absent. the alarm was given at once and the entire camp alerted. All the guards, SS men, and Kapos were sent to search for him. They looked everywhere. Inside the barracks, bedding was thrown on the floor; all possible places were searched, but they could find no trace of him. It was impossible that he had escaped during the night, and he had not been missing the previous evening. The search lasted until noon when, at last, he was found dead in the filth of a latrine.

All prisoners were punished for this. We were made to stand at attention for six hours without food or water. Legs went dead and bodies numb from standing rigidly for so long a time. If prisoners fainted or fell, they received an extra beating.

We were told by some of the prisoners who had been there longer that during the winter prisoners were kept at attention three to four hours -- until their feet froze to the ground. Many died and were taken to the crematory.

After evening callup, supper was given to us. Normally, it consisted of boiled potato or soup, and one-third pound of heavy dark bread. Once every ten days, we also given a small piece of margarine, or a dab of plum jelly, or a small piece of horse sausage. After this sumptuous repast, we waited anxiously for the gong which meant we could enter the barracks and crawl into the straw.

Starving prisoners searched continuously for something edible. The most likely place to find it was around the kitchen. We were forbidden to enter the kitchen, so a crowd milled around the area searching for bits of raw potato, cabbage, or other vegetable, which from time to time were thrown out by the men working in the kitchen. All of us had chronic headaches and hunger pangs.

We were allowed to go to the lavatory only for two hours before morning callup or after evening callup. No one was permitted to go alone. A group of eight was allowed to enter at one time. The next group had to wait until the first group came out. As there were only two latrines in our yard of 4,500 people, the time allotted was totally inadequate. The latrines were holes in the ground with no roof and only board partitions. There was no sewage system. Prisoners were forbidden to use the latrines during the day. Anyone who violated this rule or relieved himself outside was subjected to seven consecutive days of whippings at evening callup.

Most of the people were ill with diarrhea and there was no medical help. One of the workers in the kitchen had it so bad he could not control himself. The overseer reported his condition. An SS guard took the man out and ordered him to undress. The rest of us were made to pour buckets of cold water over him for an hour. The man died. Afterward, the guard sent for a doctor to certify the death.

Medical aid in our yard was provided by two Jewish doctors, themselves prisoners. They were allowed to give advice to the sick only after evening callup. A couple of hundred prisoners waited every evening to talk to these two, but only a few could be seen before the sound of the gong sent everyone hurrying to the barracks.

The help of these doctors was limited, since even the simplest drugs, like aspirin or iodine, were seldom available. What could they do for bleeding heads, broken ribs, ears torn half off? How could they cure pneumonia, diarrhea, or bodies swollen from constant beatings?

Those suffering from pneumonia, typhus or other contagious disease were sent to hospital on Field No. 1. So we were told.

The food for the sick was the same as for the rest of us. If they wanted to eat, they had to stand in line with the others. Sick-bay was the last stop. Every few days SS men moved the sick from the infirmary to the gas chamber.

Part of the Nazi plan was to appoint Jews to positions of authority, such as barracks commandants, secretaries, etc. In order to hold their jobs, they had to become as hardened as our captors. These Jews were the tough characters who had survived the cruelties of the camp, whereas the more sensitive or frail had died trying to stay alive. Often, the "boss" Jews outdid their SS masters in cruelty.

A Jew of this type was the commandant of our block. He was proud of having been chosen. He strode up and down the block like an animal trainer, wielding his whip. Hw would curse us with vile epithets. His whip had a piece of lead fastened to the end, the better to batter our heads and faces.

In each barracks a Jew was appointed "host." They were gracious characters, these hosts. If a man did not hold his bowl properly when receiving coffee or soup, our host dumped the hot liquid on the man's head, then kicked him in the stomach for wasting food.

We loathed such Jews even more than we despised the SS. Their inhumanities betrayed family, friends, their very Jewish heritage.

If an SS man or Kapo happened to overlook some slight slip-up in our work, we could be certain that our Jewish watchdogs would not let it go unpunished. They vented their own frustrations on the prisoners at every opportunity.

Some of the Jewish police in the ghetto had been of this sort. When they had volunteered to serve in the "protective police force," they thought they could be of service to their people. Little by little, however, they were caught in a moral vise. Each day's quota of captives had to be met. Each Jewish policeman was responsible, at the risk of his own life, for bringing in so many Jews a day for the kill.

A gradual metamorphosis took place in some of them. Slowly they assumed the attributes of their hated Nazi masters. They seemed unaware of the breakdown in character which was taking place in them. Others realized what was happening and deserted the police force, preferring to take their chances with their fellow Jews.

Those who remained on the force were not given the special treatment that had been promised by the Nazis, but were eventually brought to Majdanek with the rest of us in the final round-up in the ghetto.

There were both good and bad among the Jewish overseers at Majdanek. I remember one, formerly a Jewish policeman and now with us. He held perhaps the highest possible job in the office -- Field Secretary. Although I knew him to take payment for getting someone a better job, he was nevertheless a man of his word. And he did not carry a whip. That alone was enough to endear him to the prisoners. He was helpful to everyone as much as he dared.

Although I had not previously known him, shortly after my arrival at the camp he placed me in the kitchen as a potato peeler. This job was literally a life-saver, and he asked no payment of me.

My assignment in the kitchen was night shift. I was allowed to rest in the barracks during the day. Better nourishment was to be had in the kitchen, and we were not beaten as often or as severly as others. Our working conditions were much better than for those who labored in the open all day.

A number of Czech Jews worked with me in the kitchen. They were mostly kind and helpful. One of them told me that when they were brought from Czechoslovakia 14 months earlier, they were 12,500 in number. Now there were about 600 still alive. There had been epidemics of typhus, dysentery, pneumonia among them. During illness they were not permitted to lie down. When they became too weak to remain on their feet, they were taken to the gas chamber.

All of the officials in the camp were not bad characters. I remember an Aryan Pole from Warsaw, an engineer. He was a Block Commandant for a short time in our barracks. Though he had the authority to beat and punish, he preferred to make life more bearable for us. Another Aryan Pole, a doctor I had known in Warsaw, was there as a political prisoner. He shared with me the tidbits of food he was permitted to receive through the mail. A bit of sugar and a few crackers did much to lift my morale.

At the other extreme was a Czech Jew who was sadistic to the point of insanity. All of the prisoners feared him. He held the position of overseer in the kitchen. He slapped the workers in the face with no cause. I still bear the marks of a beating he gave me.

The atmosphere in this evil pit called Majdanek was one of near madness. It brought out the beast in some Jews, while others tried to hold onto sanity although under unbearable pressure and agony.

A 12-year-old Jewish boy became the favorite of the Nazis. They trained him to be an overlord, giving him unlimited power over the prisoners. This child swaggered around the camp with a whip in his hand, using it mercilessly on the prisoners -- especially Jews.

The Nazis dressed him in special clothes and high boots. He ate in the kitchen with the Kapos and slept in their barracks. His name was Boby. The boy became so depraved that he had his own parents hanged on the gallows in our Field just because they did not approve of his behavior.

Another Polish Jew held a job as block secretary. One day he beat me to unconsciousness, then pushed my head into a barrel of water. I nearly drowned.

We were surprised when we first learned there were Aryans at Majdanek. Poles, Czechs, Russian POWs, gypsies, and German criminals. Most of the Poles were well-educated professional men, as well as officers of the Polish army and police, priests, aristocrats, members of parliament, and senators. Their crimes? They were leaders of influence, and the Nazis wanted them eliminated.

(note: "Aryan" is used loosely, as the Nazis used the term.)

Relations between Aryan and Jewish Poles in the camp were generally pretty good. All were in the same boat. In the face of death, we were equals. The Polish prisoners, though, were treated a little better than the Jews. They were given additional rations of bread; they had permission to receive parcels and censored letters from outside. Most importantly, they did not have daily assignments for the gas chamber. From time to time, a few were released and went home. This gave others the hope that if they could withstand the hardships of the camp a little longer, they, too, might be freed.

The Jewish population was cosmopolitan: There were Jews from France, Belgium, Greece, Germany, Czechoslovakia, and all parts of Poland. Among them were many distinguished men from Warsaw. I cannot recall their full names, but there was a Dr. Schiper, a former member of the Polish Parliament, who worked with me in the kitchen. And Cantor Szermah form the Warsaw Synagogue. Dr. Lando, a well-known physicist and his brother, an engineer. A big "Fibra" manufacturer, Mr. Himmelstaub. ["fibra" clothing?] Mr. Kulas, a pharmaceutical wholesaler. Mr. Okon, an engineer whose wife jumped from our train. A well-known welfare worker, Mr. Wegmajster (son-in-law of a senator) and his two sons from Lodz. And a banker by the name of Gelbfish. All of these men either died or were liquidated during the first 3 or 4 weeks at camp. A famous writer, Andrey Marek, was gassed at the same time as my father.

These men were not important to me because of who they had been or the positions they had held, but because of the example they set for the rest of us: the manner in which they accepted adversity, the humbleness with which they approached the most degrading tasks, and never losing their innate dignity. They showed us how to hold onto the core of decency which separates civilized men from human beasts. Even the gas chamber could not rob them of their stature as men in whom the spark of Godliness dwells. We mourned their passing.

A few days after our arrival at the camp, as the weather was warm, our sandalsm caps, and jackets were taken away. We wore only underwear, shirt, and trousers. I managed to hide my cap. It might help to disguise me by covering my shaved head, should I find a way to escape sometime. With little clothing, even the weather became our enemy. Some of the prisoners had heat strokes, others suffered from exposure to the rain.

Every morning at callup time, the bodies of those who had died during the night were brought out and laid in their proper places in the line, so the numbers would tally for the count. Nazi thoroughness. In addition to the "natural" deaths, there were many "selections" daily. A swollen leg from a beating was sufficient reason for a prisoner to be sent to the gas chamber. Those selected had to stand to the left. We all knew what that meant.

Selected prisoners were kept in the "Barracks of Death" sometimes as long as eight days before they were marched into the lethal chamber. Eight days waiting for death. The gas chamber and crematory were running overtime, but still could not keep up with the load. The odor of roasting bodies hung heavily over the camp.

Women were gathered on Field No. 5. If possible, they fared worse than the men. Their work was the same as ours: aimed to exhaust and kill. I learned from letters smuggled to me that Luta and Ignas were suffering miserably. There were no bunks in the women's barracks. They slept on bare floors with few covers. They had to fight for their food. It was not apportioned to them. The strong women ate; the weak went hungry.

I heard my son was ill with an intestinal disorder. Luta wrote that she had sold her American $20 gold pieces for 3,000 zlotys in order to buy him some food. The following day the Nazis took the money from her.

On May 23, 1943, all mothers with children, 2,000 all together, were made to stand at attention from six in the morning until midday. Then they were loaded onto trucks and sent to the gas chamber. We learned all this from the men who delivered food to the women's part of the camp. I was frantic. I had to find out if Luta and Ignas were among that day's extermination. Three times a day food was placed on platforms which were then pulled by the kitchen workers into the women's field. That evening, I went along with them.

When we arrived at Field No. 5, I saw my sister Stefania at a distance. When she saw me, she came near enough that I could hear her. She told me that women with children were given a choice: Let the children go alone to be gassed-- or go with them. Luta would not part with Ignas. They were both dead. My dear brave Luta! My beautiful boy! Oh, God, now take my life.

As we pulled the platform back from the women's field, an SS man broke two sticks across my back. I felt nothing. I probably would not have felt it if they'd cut off my leg. As I pulled my heart seemed to explode in my body. Luta! Ignas! But I lived. Again, I thought there is no God

The following day 2,000 bodies were burned on the open field. The crematory was too small to accomodate such a number. They piled bodies in a ditch, sprayed them with kerosene and burned them to ashes. The smoke from the mass pyre rose like an evil cloud. The living wept for their loved ones. I wept for my dear wife and son.

My loss almost unbalanced me. I could not sleep. I tried to project myself into that final scene. It was torture. The mothers and children, per Nazi system, were made to remove all clothing before entering the gas chamber. This had to be saved for later prisoners, and it was more efficient to have the selected undress before they died, so the corpses would not have to be disrobed later. My beloved must have taken our boy by the hand, trying to comfort him as they entered the killing room. How strong she must have been for Ignas. How terrified my son.

I agonized over these images night after night. I peeled potatoes as though I were slicing skin off a Nazi's body, gouging bits of root with my paring knife, wishing they were Nazi eyes.

My sole consolation during this time was the smuggled notes my sisters sent. They wrote that they were no longer human beings, merely automatons living from day to day. They knew they were condemned, and there was nothing they could do to prevent their doom. I totally shared their thoughts and fears. But not their resignation, though I was unaware of it at the time.

The SS men were bad enough, but their female counterparts were more deadly, if you can imagine. The term "woman" as applied to them was a crude joke and an insult to the rest of womanhood. They were killers in skirts. They wore high boots and carried pistols in their belts, whips in their hands. They were a new breed, devoid of all feminine attributes, their faces obscene masks. The first day in camp, when we were taken to the showers, one of these Nazi cows came among us, completely nude, parading herself for us. Hitler had decreed that any German woman having relations with a Jew would be guilty of "Rassenschande," race-shame. But what Jew worthy of the name would commit race-shame with such as these?

There were other women in the camp. While we were still in the ghetto, we heard that attractive Polish girls and other young women were disappearing from the streets of Warsaw under mysterious circumstances. Now we knew what had happened to them. They were here at Majdanek, victims of Nazi white slavery. We saw them. They were housed in a brick building surrounded by a high barbed-wire fence, guarded at the gate by SS men. As they walked in the gardenthey looked well-fed, these young women, kept in good condition for the pleasure of the SS beasts.

The notes from my sisters suddenly stopped. Some of the male prisoners who worked beside the women's field acted as postmen between the two camps. When I asked them why I had not heard from them, they gave no straight answer. Had they seen my sisters? No. I felt positive I would never see my sisters again. Their deaths severed the last earthly ties for me. In just a few weeks' time I had lost all of my loved ones: Orphaned, wifeless, childless, bereft of my entire family. I alone survived.

At this moment in May, the most beautiful month of the year, when everything comes to life, I died within myself. For as long as I live, May will be a month of mourning. But what prospect could the future hold for me if I should survive? I prayed that I might join my loved ones. I considered suicide.

Others had taken this way out. The easiest way was to throw yourself against the electrified fence surrounding the field. This was known as the "lane of death." The fence stretched between towers that were manned by Ukrainian guards armed with machine guns. So the odds were good that you would be killed before even making it to the fence. One way or the other, sudden death seemed preferrable to the torture of the camp.

Yet, as I nursed the thought of suicide I was emotionally conflicted. I wanted to be dead, but I wanted vengence. Vengence required me to live. It was the purpose of the Nazis to kill me eventually -- why should I help them? I determined to defy them and to live. Now I had a reason: to see the enemy destroyed. I wanted to live to witness the destruction of the Nazis and their punishment for crimes against humanity. To do this, I MUST ESCAPE.

During my night work in the camp, I sometimes was able to stroll into the yard and look around. Escape seemed impossible as the camp was surrounded by a double fence of electrified wire, about 6 meters (19 feet) high. Big reflectors were trained on the fence and the "forbidden lane" (the suicide lane). A needle could be seen in that bright light. The slightest movement could not go unnoticed. And the trigger-happy Ukrainian guards kept a close watch from the towers.

On the other side of the fence, SS men and Ukrainian guards with trained German police dogs patrolled ceaselessly. Even if one were lucky enough to get over the fence alive, he would be picked up by the patrols on the outside. Further, all the nearby roads and lanes were guarded by Ukrainian and Lithuanian patrols. The camp's defenses seemed impregnable.

Some prisoners who had been at Majdanek much longer than I insisted no one had ever successfully escaped. Not only the would-be escapees, but their outside helpers were caught and executed. But I was not discouraged by these seemingly insurmountable difficultie. Perversely, they served to spur me on to find some new avenue of escape.

It was madness, I knew, to dream of escape, yet I also knew I must try. During this time I became quite self-contained. I peeled potatoes and spoke to no one.

At the beginning of June, I heard of a group of 80 Jews from Majdanek who worked under guard at a sawmill outside Lublin. This was something to think about while I peeled potatoes.

Some people I knew were in this group. I learned that occasionally they were able to talk to Poles from Lublin who worked at the mill. Through them, the Jewish prisoners were able to buy a little food. They also said that the work in the mill was much easier than at the camp.

Trucks for the sawmill workers left camp early in the morning, returning late at night. This group of Jews wore special blue and white striped uniforms with the Star of Zion and large identification numbers printed on the fabric.

Soon I made contact with a Kapo, the leader of this group. He wanted 500 zlotys to arrange for my transfer from kitchen duty to his group.

All my money had been confiscated, and I was unable to smuggle any into the camp when I came in. If a prisoner had money, a Kapo could buy him bread, butter, sausage, or other items. Also, he could mail or receive letters, always for a certain price. There were ways of making a little money in the camp, strange as that may seem. At the lowest levels, running small errands or passing messages. But I had contact with several people of influence. Through them, I was able to place some prisoners in better jobs, for which the prisoners paid me small sums for the favor. Little by little, I managed to save near 1700 zlotys (about $15.30).

I paid the 500Z the Kapo asked, but he reneged and demanded more for me to be in his group, said he used the 500 for a few drinks. I charged the loss to experience and looked for other opportunities.

Meanwhile, for when I would be able to go with the work group, I knew that I could not take 10 steps on the street with my clipped head and striped uniform. A fellow prisoner had baggy long underwear that looked much like loose white trousers. I bartered for them with my own tighter long underwear and one kilogram of bread. And I had hidden in my pocket the cap I'd been issued the day I had arrived. We were told to turn them in the day we gave up everything but shirts, trousers, and underwear. My cap was not discovered. Bit by bit, I had scraped off its painted red stripe. Now it looked like any other workman's cap. To complete my escape outfit, I exchanged my shirt with another prisoner for his rubaszka -- a wide Russian blouse buttoned up to the neck. Wearing these items, I could easily be mistaken for a Russian peasant.

I knew these preparations were dangerous. Had any camp authorities discovered I'd removed the Jewish identification stripe from my cap, I would have been hanged.

I now tried through another man to join the outside work group. I paid him the 500Z and he did not fail me. Every week the work group was reshuffled. Each newcomer paid the 500z, and the Kapos or guards pocketed the money weekly.

I modeled my new striped uniform for my friends in the kitchen. They tried to discourage me, certain that leaving the kitchen job was the biggest mistake I could make. There was no better job in the camp than kitchen work. When our kitchen secretary learned I was leaving, he gave me a severe beating. I had to pay him 150Z to keep him from canceling my transfer. I explained that being in contact with outside people might enable me to buy items that I could resell in camp at a good profit. This sounded plausible to me... and logical to those who might benefit from my bringing in outside items.

Once a week we went to the bathhouse. While we were undressed, our underwear was taken to be deloused. The exact same garment was not often returned. As I could not risk losing my baggy pants, I did not give them up for two weeks. Had I been caught, the punishment would have been 25 lashes...PLUS, I would have lost my escape outfit.

Bathhouse scenes were macabre: ravaged and wasted bodies, the ashen pallor of starvation, exposed bones, black spots from beatings with sticks and whips. And, yet, we had to take the showers. Everyone had lice. The "cleaned" underwear, straight from the oven, still crawled with lice.

In the hall outside, where we waited naked for the return of underwear, a sharp draft from two paneless windows caused hundreds to catch colds, and many to die from pneumonia in their weakened conditions. Even in summer.

[There were a lot of young men at Majdanek who had been sent from Treblinek. Their wives and children had been exterminated there and the men shipped here for the slow death that Majdanek SS excelled at. Majdanek, we learned, was one of the worst Nazi camps. Jews from Dachau said Dachau was like a hotel. After spending 15 months there, they all looked comparatively well when they arrived. I wondered what even a few weeks at Majdanek would do to them, how many would survive a month or two.]

At last the great morning came when I would go to work outside the camp.

Eighty of us in our striped uniforms marched in files through the camp, in the direction of the highway. We stopped at the gate where we were counted and re-counted, and each man given a thorough search. Under the heavy escort of several SS and more than two dozen Ukrainian soldiers armed with light machine guns, they loaded us into two trucks.

As we rode in the direction of Lublin, I drew clean air into my lungs for the first time in six weeks. Free from the stench of roasting human flesh, the clean ar was intoxicating.

Passing through the streets of town, we stared dumbly and numb at the burned rubble and devastation of the ghetto. Wherever Nazis took a city, this was their method in the ghetto: burn whatever was left standing.

Beyond the ghetto, women strolled the streets with their children, tended flower boxes in windows, smiled at passersby. Though not at us. They didn't appear to see us. Did these seemingly happy people even know they lived one mile from Hell? Is it possible they did not know? Is it possible they did not care?

A wave of bitterness rose in my brain, like a black tide. The full meaning of freedom engulfed me as if I thought it for the first time. I was ready to fight and to die for my right to freedom. Freedom. The word is understood fully only by those who do not have it.

On the outskirts of a Lublin suburb, we came to the sawmill, the lumber yard where we were to work. On one side it was bordered by a plain, ordinary street. This street became my window to the world.

Our police escort surrounded the yard on all sides, just outside the fence. Inside the fence, SS stood at strategic points. A Ukrainian guard stood on the highest pile of lumber in the yard; from there he could observe everything and watch every movement of the prisoners.

As we were unloaded from the trucks, the overseers divided us into small working groups. Particular tasks were assigned to each group. All members of a work group were responsible not only for the amount of work accomplished, but for each other.

On the first day, I paid particular attention to the neighborhood in the vicinity of the sawmill. Bare fields edged three sides of the yard, with fences patrolled by guards spaced about 20 meters apart. Although it was not fenced, the street side was also constantly patrolled. The street was closed to civilian traffic, and a railway spur to the mill ran along the other side of the street. Sure that the street side, used by free Polish employees, those whom we relied on to make purchases for us or to smuggle letters, would be the only possible means of escape, I began to form a plan.

As they entered, free workers had to show their passes to the guards at the gate. These documents proved they worked in the yard or had official business to conduct. Over time, I noticed these documents were checked carefully when a worker entered, but seldom when he left. The outside guards, it seemed, took it for granted that passes were checked and approved. I figured if I could just get to the street and walk freely, I could escape unchallenged. It would be my only chance. All I needed to do was to watch for the right moment.

It was not to be easy. Officers and the Kapos were everywhere. And prisoners watched one another suspiciously and even more carefully than the SS. The reason for this was the regulation that said if a prisoner attemtped to escape, every second prisoner in the unit would be hanged. Forty men would pay with their lives, as well as myself, if I should try to escape and fail.

For the next six days there was no opportunity. Two of those days, rain prevented any attempt. My pseudo-peasant outfit would need a coat in the rain. I had to wait for better weather. During this time workmen began building a fence on the street side. Soon we would be fenced on all four sides and my chance for escape would become negligible.

Then, on Sunday June 20, we learned that 2500 healthy young Jews were to be sent to a synthetic rubber factory at Oswiecim. I had heard that workers at this factory died off quickly because of the poisonous chemical acids in the process. The qualifying for this crew started at once, but as it was late in the day only 500 were selected. The next day the selections would continue until the quota was filled. I felt certain to be picked for this crew. If I were going to escape, I had to hurry.

Monday June 21, the last day of my week's assignment at the lumber mill, I went to work as usual. But I was determined to escape that day. . . or die trying.

Just before the noon break I told my overseer that I had to use the lavatory. On the way, I jumped between piles of lumber, tore off my striped uniform so that I was in my "Russian peasant" costume, stuffed the uniform deep among the lumber, put on my cap and a pair of old shoes I'd hidden there (we worked in wooden shoes)-- and started toward the gate.

I was just about to step out from my hiding place when I saw the head overseer walking nearby. Holding my breath, I waited a moment for him to pass, a moment that seemed like a year. Then I heard our unit overseer calling me back to work. That was the final spur.

I looked left to right. The SS man at the right side of the street was checking someone's pass. Good. I walked, outwardly calm and confident, to the middle of the street in front of the lumber yard. The patrolling SS on the left side had just turned and was walking in the other direction, his back to me. I prayed to Almighty God that the guard would not notice me.

As I arrived at the left side of the street, the SS man suddenly turned and saw me. I met his gaze calmly and walked slowly and deliberately in his direction. The street was completely empty, but I felt that thousands were watching.

As I approached him, he looked at me with a smile and spoke in Polish: "Going home so early?"

I was sure I was caught and that he was being sarcastic.

Taking a deep breath, as though exhausted from the heat, I answered: "Yes, I am going home to have some lunch and drink. It is too hot to work more today.

He did not stop me, so I walked past him, my heart pounding in my throat.

He called out to my back: "Good appetite!"

Over my shoulder I said thank you, and kept walking.

Those moments, I felt hypnotized. It took all I had to command my feet to walk, to keep walking. Now I had passed the officer and was on my way.

I did not dare turn nor look back, but I had an overpowering need to know if I were being followed. I bent down as though to tie my shoe; between my legs I saw the street was still empty.

As I walked on, I remembered I still wore around my neck the piece of tin bearing my identification number. I unbuttoned my shirt, tore off the badge and buried it. I was a long way yet from being free.

I crossed the street and walked the railway tracks as though I were playing a game: but it was so as not to leave tracks on the damp ground.

The first person I met was a girl of about ten. Her fair hair and blue eyes pained me with the memory of my son. I asked her where a certain street was, and she replied with a child's confidence that it was quite far, but since she was going to school in that neighborhood, she offered to walk with me. I was deeply grateful because I didn't want to ask an adult for directions and arouse suspicions.

I managed to keep our conversation flowing so that it would seem to those we passed that we were relatives walking together. With each step I felt the eyes of strangers burning into my back, heard ominous whispering. But my paranoia was utterly justified, so I made efforts to keep it under control. At last we reached the street I needed and we said goodbye. I thanked her very much then, and I shall never forget the sweet child who gave me my first help toward freedom. Sometimes I think she may have been an angel.

Next, I looked for the shop of a customer of our leather goods factory -- one to whom we had extended credit and who still owed us money when our factory was closed.